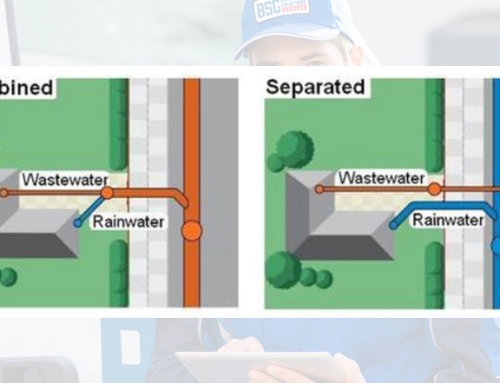

Some unlucky homeowners have their house’s plumbing attached to sewer systems that are “combined.” For these houses, the same municipal sewage pipes that whisk away fecal matter at the flush of a toilet also carry rainwater. But when there’s a heavy storm, combined systems have more fluids than they can carry. Oops: that’s when rainwater and sewage can back up into basements. That leads flood-ravaged homeowners to spend weeks scrubbing their basement walls with bleach, wrestling armchairs soaked in flood water up the stairs to throw out, and frantically sniffing at coffee tables with a funky smell. One alternative: if the homeowner has a backwater valve, this will help to prevent water from backing up into a basement.

Combined sewers are an outdated sewer method. The conundrum is that older parts of cities still have combined sewers, and municipalities have to balance the cost in taxpayer dollars to replace them against other city services. Municipalities also have to balance the inevitable basement floods that occur repeatedly, to the great frustration of citizens who just want to use their basement to store out-of-season clothes without a flood leaving mould and mildew.

A poopy case study

One example of a city’s combined sewers is Hamilton, where the city’s downtown has an older sewer system. These homeowners have both a sewer connection coming from their house, and a storm sewer connection coming from the catch basin on the street beside them, that connect to one trunk sewer. During heavy rainfall, it’s more liquid than can be processed at the sewage treatment plan.

To hold onto the massive influx of stormwater mixed with sewage during heavy rain, the city built overflow storage containers. They’re literally giant tanks. But record-breaking rain in Hamilton in January 2020 quickly blew out the capacity of the overflow storage tanks, and that led to significant flooding. “This event produced the highest January rainfall on record for this part of the province and resulted in substantial flooding in a number of communities in the northern and central portions of the watershed,” read a release from the conservation authority. As climate change disrupts “typical” rainfall patterns, it’s difficult for municipalities to predict how much stormwater will surge through combined sewer systems.

Combined sewers and flooded basements

A January 2011 study by Clean Air Partnership found that in Hamilton, heavy rain can overwhelm combined sewers and cause flooded basements: “After periods of heavy rain, the storage capacity of combined systems can be overwhelmed, forcing the mixed waste to backup into homes or be discharged without treatment.” That means mixed waste will backup into the lowest point of a house.

The report notes repeated flooding of basements in Hamilton during rainfall is exacerbated by poor house design, including a lack of backwater valves, aka back-flow preventers: “Basement flooding damage is exacerbated by poor design of existing houses with garages sloping towards them, basements lower than the sewer mains, or the absence of back-flow preventers.”

While many home design decisions have already been made during the build process, some flood-prevention features (like a backwater valve) can be added to an existing house.

Backwater valves have your back

Sometimes called back-flow preventers, the ingeniously simple design of a backwater valve will help to prevent the overflow of a combined sewer system from flowing into a house’s basement during a storm. During normal operation (read: dry weather), the hinged flap is “open”, allowed a house’s greywater to flow out. But when water tries to flow backwards into a house (read: rainstorms), the hinged flap will “shut”, keeping out the combined storm water, sewage and greywater.

One thing to remember: the back-flow preventer or backwater valve requires regular maintenance to ensure it’s operating as designed. A checkup twice per year can ensure it’s fully operational, whether the house is connected to a combined or separated sewage system.

Without a backwater valve, homeowners could have a sad answer to the question: baby got backflow?

Every city has combined sewers

While it’s impossible to know if every city has combined sewers, they’re a problem in cities like Ottawa, Toronto, Kingston, Halifax and Winnipeg. For example, it was a common practise in Edmonton before the 1960s because it was cheaper to build one sewer system than two. Combined sewers are still found in older parts of cities, although they’re no longer being installed.

As climate change increasingly brings massive rainstorms, combined sewer systems can face a surge of stormwater. Cities have a Plan B: they release the combined sewer system water directly into waterways. But compared to the Mad Men era, modern environmental scruples don’t appreciate raw, untreated sewage being dumped into the same rivers and lakes used for boating and swimming. That’s why municipal governments try to solve the problem of combined sewers, as Hamilton did with storage tanks.

Goodbye to sewage among the fishes

It’s expensive for municipalities to dig up and separate combined sewage systems, but it can be done. Vancouver is working to install separated sewer systems in five neighbourhoods in 2020. When this happens, homeowners must pay to upgrade their own sewer connection from their house, so that rainwater from their property can flow in its own pipe to a waterway and the fishes who live there. Sewage and greywater will flow to a treatment plant. And hopefully, none of it will backflow into the flooded basements of homeowners. But, with the increasing volume of major storm events given climate change, who wants to take that chance? It’s much better to have a backwater valve installed and regularly maintained, thus preventing sewer floods from occurring in your basement.